Ransom Center Scholar Addresses Climate Change via Poetic Podcast

- Mar 11, 2025

- Danica Obradovic, Harry Ransom Center

[Editor’s Note: This article is part of a Texas Global series created in partnership with the Harry Ransom Center, chronicling the stories of scholars who visit Austin from across the world to conduct research in the center's archives as part of the Ransom Center Fellowship program.]

Jayme Collins recently traveled to Austin with her pup in tow for a monthlong fellowship at the Harry Ransom Center (HRC), a humanities research library and museum at The University of Texas at Austin. A citizen of Canada, she set out to study the HRC’s uncatalogued papers of bookbinder and conservator Peter Waters for her podcast, “Archival Ecologies,” and a companion book project.

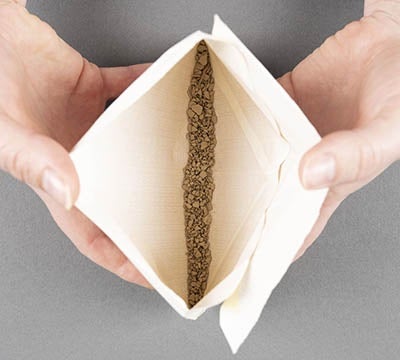

But she hadn’t expected to stumble upon physical evidence of an historic 1966 flood in Italy: an envelope of dried mud contained in a zippered plastic bag, tucked within the collection. Waters had saved the sample while leading a preservation team in Florence to restore the Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale di Firenze.

Collins, a postdoctoral researcher at Princeton University, was the first scholar to explore the unusual collection since its relocation to the Ransom Center in 2019. Waters developed and documented many standard practices around book conservation while he served as chief conservator at the Library of Congress in the 1970s, so his papers are key to Collins’ research on archives and ecological phenomena.

The Language of Disaster Recovery

“Archival Ecologies” was created by Collins with production support from Blue Lab Media, an environmental research, storytelling and art group. The series contends with the physical loss of cultural heritage material due to climate change and identifies the distinctive responses and processes of communities who are recovering from environmental disasters.

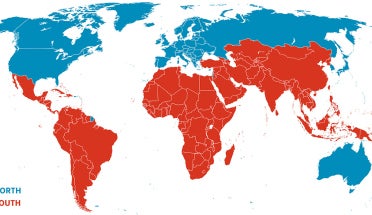

“One of the things I noticed in my research is that communities turn to cultural material — often, cultural material that is lost — to grapple with what climate change means and looks like in their local communities, even when climate change isn’t necessarily the framework they would use to understand their experiences and observations,” Collins said.

She considers climate change “a massive concept” that encompasses a huge amount of human history and inequality. The memory or restoration of these keepsakes can facilitate more nuance and varied cultural understandings of it, she said.

Aiding ‘Sick’ Books

Collins pays attention to rhetorical habits when studying the development of conservation practices. For instance, in the Waters papers, she noticed “a lot of language about books being sick.” She explained, “Damaged books are sick books. Conservators talk about books having a head and a tail … There’s language around liveliness that ties book conservation to other movements for environmental health.”

Collins studied English literature at Northwestern University. Her dissertation concentrated on material poetry; similarly, in her home, she uses a loom — a cultural object evocative of patience — to interlace threads into a unified meaning. The episodes of “Archival Ecologies,” too, are reminiscent of deep poetic investigation, the narration reflecting cadences and rifts of language, something affecting and sublime.

“I think of poetry as a container for thinking about long histories of environmental thought,” she said. “Poets have turned to those ways of knowledge in order to understand the complexity of what environmental crisis looks like or how it happens when it lands in the contemporary moment.”

Collins’ podcast carries the resonance of art, and she conducts extensive journalistic fieldwork and research for each season, interviewing people affected by environmental disasters that are exacerbated by climate change. Season One delves into the aftermath of a wildfire in Lytton, British Columbia, a village of about 250 residents.

Fellowship Community at the HRC

While archival research is a special undertaking for an enthusiastic scholar— and vital in understanding historical phenomena — it can also be a solitary and disorienting experience. Spending an hour in the archive can lead to days of uncovering astonishing items from the past, resulting in an often-irresistible itch to tell someone immediately, even amid the quiet restraint of the library.

The Harry Ransom Center strives to provide social support for the 60 fellows who visit the center annually. There are weekly coffee socials, evening outings, and other programs and events that complement the experience and ground it in interaction with other scholars, staff and the UT community.

Collins, for instance, participated in the fellowship program’s works-in-progress research series, "Familiar Terms." With a lens on creativity in scholarship, the series connects staff and researchers by featuring the work and archival finds of current fellows at the Ransom Center.

“The opportunity to connect with other fellows and with library staff outside of the Reading Room was fun and also provided a lot of methodological reflection and energy to my research,” Collins said.

She even consulted with a field specialist, Associate Director for Preservation and Conservation Ellen Cunningham-Kruppa, who brought Waters’ papers to the Ransom Center.

Localized Listening

Collins’ practice of centering communities is imperative, with the effects of climate change cropping up relentlessly. She believes the news media often dominates the conversation with templates for catastrophic natural events, but they don’t always reflect the local experience.

“I think that what is true for Lytton isn’t necessarily true for Los Angeles,” she said. “Part of that is, they are shaped by some similar histories and some very different histories. And so, the terms on which those communities choose to navigate toward the future or choose to ground their cultural knowledge are going to be different.”

Collins experienced her own scare as a teenager in a town in central British Columbia called Kelowna when it was devastated by a wildfire in 2003. The fire sparked in Okanagan Mountain Park, just south of the town, and went on to burn about 240 homes in her neighborhood. She and her family spent two weeks evacuated from their home that summer. In an 11th-hour effort, the city made a plan to bulldoze a 100-meter strip of land to act as a firebreak.

“They figured, once it got past this place, they would lose the whole town,” she said. “Our family home was in that area, so it was set to be, essentially, bulldozed … An hour or a couple of hours before they started this work, the wind changed direction, and it blew the fire back up into the hills. Our home was spared.”

Preservation is Personal

It’s heartrending to absorb these stories, to realize how quickly they take shape and how two different outcomes are separated by a flash. Collins described the feeling of dislocation caused by the fire, which continued to live in her body. But, she said, she finds value in peaceful approaches to understanding climate change: “the everyday actions, the acts of cultural preservation, the storytelling.”

She is invested in describing these events from local perspectives and hopes to avoid applying her own framework to community timelines. When she describes her process for writing podcast episodes, it’s apparent that she possesses the empathy and finesse required for this work.

“I come back from the field, from working in the communities and interviewing, with an overwhelming amount of material,” said Collins. “And I also come back with all these stories and all these reflections of people. I just hold those in my head and in my body, and I sit with them.”

Visit the HRC website to learn more about the Ransom Center Fellowship Program.